Inside the Wondrous Studios of Three Pakistani Artists

[ad_1]

KARACHI, Pakistan — Artists’ studios enthrall me. Dusty tools, unusual raw materials, out-of-print books, and bizarre found objects: Here, everything flows together as a unique and creative diorama. Among many others, three Karachi-based artists — Shazia Zuberi, Ayessha Quraishi, and Marium Agha — continue to expand the scope of what I like to call “processual knowledge” in studio artmaking in Pakistan.

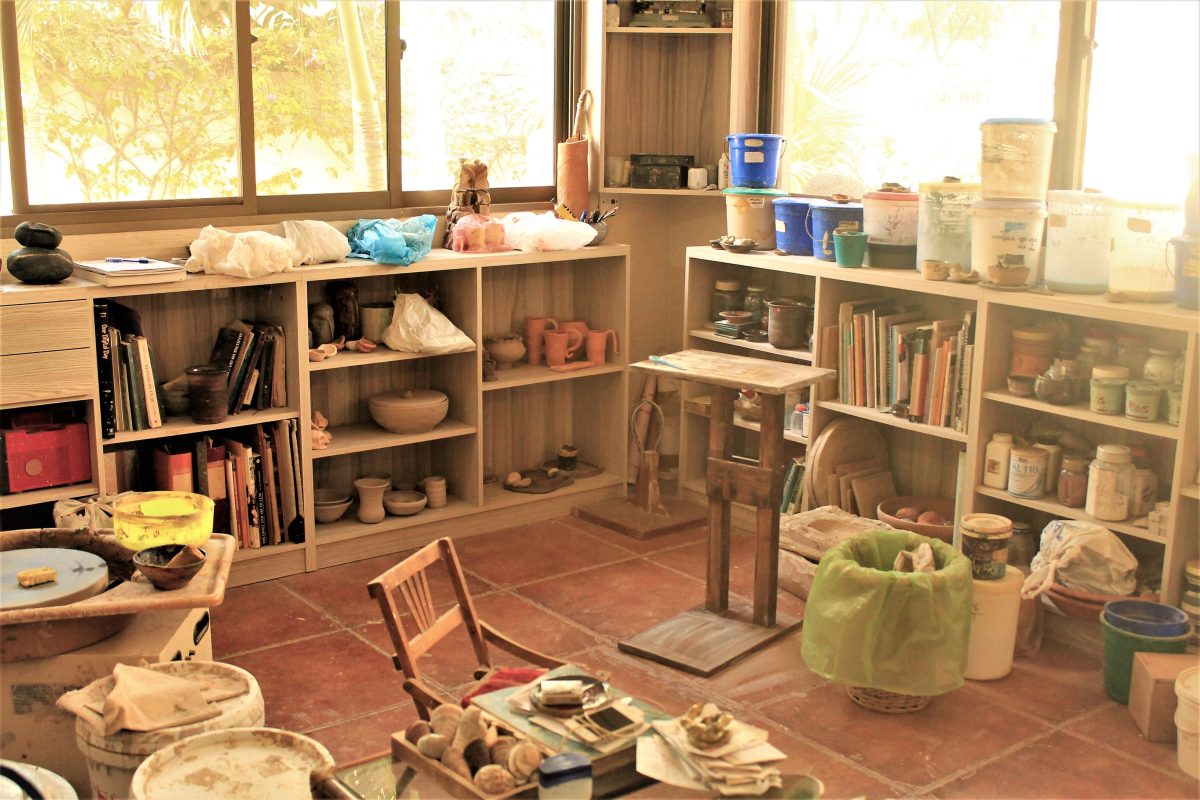

I started observing Shazia Zuberi’s ceramic practice a few years ago. With clay works and mixtures, tins of brushes, self-made glazes, a potter’s wheel, and books gathering dust, Zuberi’s average-sized indoor ceramic studio is a practical space. The room connects with a patio that acts like a personal exhibition gallery where the artist stores some works and semi-prepared clays. Another outdoor spot in her home stores her electric kiln. All these sections act as a composite space facilitating the transformation of ceramic into art for exhibitions or into functional pieces promoted via the artist’s pottery brand.

Studios can reflect an artist’s individual creative genius or illustrate physical processes that may come to represent their signature methods. Sometimes deemed an ivory tower of production and other times a transmuting space facilitating a fluid exchange of people, ideas, materials, and objects, the artist’s studio has been embraced as a private sanctuary, a collaborative setting, a factory, or an exhibition area, among many other roles.

The function of the contemporary Pakistani artist’s studio is unbound. This studio may be an enclosed space (a room, an attic, etc.), or semi-enclosed (a shed, a patio, a garage). Some studios are dimly lit and less-than-glamorous while others may be bright and organized. Not all Karachi-based artists work from such spaces; pantries, stores, or parts of their bedrooms are artistic havens for many. Presently, more Pakistani artists are practicing from their dedicated ateliers than ever before as they engage with historical traditions, modern approaches to imagery, and contemporary manipulation of found objects in the global art scene. Through documenting different studios in Karachi, I realized that idiosyncratic artistic processes converge with artists’ unique working environments to influence the artwork — formally and conceptually, and sometimes unbeknownst to the artists themselves.

Zuberi’s works, which I like to call “geographical ceramics,” are interventions that weave her travels, map-making, chemical experimentation, and sketches. Evolved from her figurative ceramics in the late ’90s and 2000s, her contemporary stylized, mask-like forms (“the heads”) and glazes on bowls are inspired by her wide journeys within Pakistan.

One day in her studio, she showed me a patch of textured, mud-colored grass heaped in one of her ceramic bowls. “Look, the grass from the Deosai Valley, up north,” she told me. “See how it smells?” I poke my nose in it and pick up a faint scent.

“I pick these tokens from my hikes and bring them to the studio. And then I like to create finishes that evoke nostalgia of our primitive lands,” she continued. As the artist interacts with these little items, the studio acts as a mediating space between her hikes and material processes that morph into ceramics, serving as visual records of terrains and their interaction with humans.

For artist Ayessha Quraishi, an organized workspace is essential. A white palette dominates Quraishi’s living room and central studio space. A wooden table and a smaller console serve as her principal workspaces. Paints and pigments in recycled coffee bottles, tools, and books are lined neatly on a shelf against the wall. Most of the premises operate as one unique site of social and professional engagement, storage, and artmaking. Everything is elegant and serene. Frankly, I have little desire to depart.

Since the ’80s, Quraishi has been cultivating an abstract visual expression that makes no reference to global abstract art movements. Her paintings suggest an ontological confrontation with memory and mindfulness, and her processes are often intuitive. “I cannot work without an organized studio,” she said. “The process of knowledge-making is immaterial here, it happens in my head and within this space while I am mixing the paints, laying out my boards, and so on. Everything is about the notion of ‘space,’ it is the concept behind my work and my processes.”

She continues to explain how her methods are tied to her abstract painting. “I always apply paint with my hands. This allows for an immediacy that the brush does not grant. During the painting process, except for my immediate space, of course, my studio stays as organized as this,” she adds mischievously. For Quraishi, whose works prioritize ideas of the immeasurable over the role of material, the studio may not be directly involved in the making of “concept,” but it is yet a carefully designed space that facilitates the “physical” image-making process.

The definition of what constitutes a contemporary studio in Karachi, where the art scene is wide-ranging, can be broad and fluid. For example, must a studio always be dedicated to visual art practice? Considering the tradition of crafts in the country, its amalgamation with visual arts, and artist-run entrepreneurial setups, when is the studio adopted as a workshop or a karkhana (factory)?

Marium Agha’s textile-based works center around ideas of love and desire through experiential realities of women. The artist finds tapestries in Karachi’s bazaars that often depict imagery of lovers’ rendezvous in the woods. She unsews their original threads, splashes inks over the surface, and then embroiders new strings in this semi-altered exterior using an ari (embroidery needle). The remodeled tapestries emerge with new meanings, its figures appearing to be “melting down” in the finished works. Agha applied these methods to create her piece “Hear Hear” (2021), which won the Sovereign Asian Art Prize in Hong Kong. “When I deconstruct something like this, I create an opportunity to rewrite the narrative,” the artist told me.

Agha started out from her “bedroom studio” in the mid-2000s. For the past five years, she has operated from a studio outside of her residence that functions as a hybrid network of creation, deconstruction, removal, intuitive thinking, and rewriting. In this site, existing knowledge of tactile methods like embroidery and sewing, as well as digital image reconstruction and found images, are progressively tested and new processes are continually developed.

While we chat, she is constantly managing her assistants for her design and clothing lines. “This space is my workshop/factory/atelier where art and work is constantly churned out,” she said. “It has an endless stream of incoming artisans, visitors, photographers, writers, and thinkers.” The physical boundaries demarcating areas for making artworks, artisans, profitable products, and their photography are well drawn; however, their proximity allows overlapping of processual knowledge and interconnected functionality.

Contemporary artist studios in Karachi prioritize pragmatism; many resist traditional understanding of spaces with singular purposes. Often the studio links art, craft, and design where processes are controlled by the visual artist and professional artisans, yet they also welcome a rethinking of images. Studios also shift to accommodate similarities with contemporary craft-based workshops (where ceramic and embroideries are sources of income for artisans in all Pakistani provinces). Some distinction can be drawn between these practitioners. For instance, a successful craft specialist works within a semi-enclosed “workshop,” where procedures are controlled. To the contrary, a studio ceramicist is engaged with formal and conceptual inquiries of their works, as seen in Zuberi’s ceramic studio that boosts experimental processual knowledge. Finally, studios like Quraishi’s foster theoretical models of artmaking, and ideas of form and space, over the role of materiality.

But they all share one unifying trait: They are major sites of transformation. Here, knowledge-making is a collaborative and progressive process connecting postmodern mergers of art, craft, readymades, and materials. No, the studio may not always be the birthplace of the art in question, nor do all artists work from one. Yet, works fashioned in a studio are imbued with meaning prior to viewers lending their interpretations. All through the makers’ hands and the power of their surroundings.

[ad_2]

Source link