When the parody image ‘The Last G7’ went viral on Chinese social media in June of 2021, it made international headlines for insulting the G7 summit, the West and Christianity, ridiculing ‘double-faced’ Australia, bashing Japan over Fukushima water, and offending India’s COVID19 situation. There was enough satirical symbolism and detail in the image to offend virtually any country that was -implicitly- portrayed in it.

Some media headers suggested the image was created by Chinese state media, others said it was done by ‘Chinese trolls’ or Chinese authorities.

The image was actually created by a Chinese computer graphics illustrator from Beijing who is active on social media, where he also sells his digital art online.

Online political satire in China has been around since the early start of social media in China and is often seen as a form of online activism. In media articles and academic literature focused on online political satire in China, the phenomenon is often discussed within the framework of censorship and dissidence, as a practice of resistance against Chinese authorities. Political satire can exist in many forms, from funny word jokes to catchy songs, from viral gifs to sophisticated cartoons.

Renowned Chinese political cartoon artists such as Badiucao (巴丢草), Hexie Farm (蟹农场), Kuang Biao (邝飚), and Rebel Pepper (变态辣椒) were previously active on Chinese social media platform Weibo, and their accounts were shut down dozens of times before publishing their work within China’s online environment became virtually impossible.

These artists are known for drawing cartoons that criticize and mock Chinese leaders, the central government, or their policies. Their work fits the narrative of online political satire being used as a weapon to resist authoritarian rule in spite of the highly censored online climate they exist in (Shao & Liu 2019, 517).

What exactly is political satire? It is “a specific form of criticism that ridicules political figures, events, or phenomenon” (ibid). Visual political satire is especially relevant within the context of Chinese social media because images allow for a creative form of expression, an outlet to critique political events, that is harder to detect by online censors than the use of potentially sensitive words and terms.

But what if political satire does not critique the Chinese party-state at all? What if it actually does not conflict with party ideology, or even suits the narratives that are propagated by Chinese officials?

Recent Examples of Chinese Political Satire on Social Media

In late December of 2020, a photoshopped image of an Australian soldier murdering a child stirred controversy on social media and beyond. The soldier, who is holding a knife to the throat of a child, is standing on an Australian flag, the shadows of bodies can be discerned lying on the floor. The image – which alluded to the report regarding unlawful killings of Afghan civilians and prisoners by Australian troops – was shared on Twitter by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian. The controversial post led to Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison demanding an apology from China.

The computer graphic by Wuheqilin that was shared on Twitter by a Chinese official.

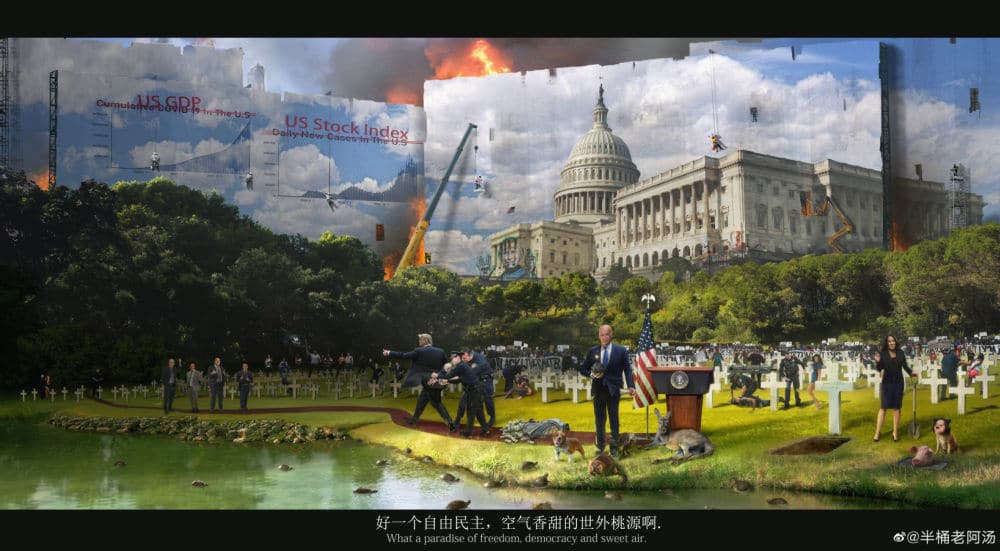

In January of 2021, around the time of Biden’s inauguration, another satirical work was shared on Twitter by a senior producer of CGTN (@Peijin_Zhang) and others. Like the earlier image, this political satire was also full of details and symbolism. It shows American President Biden holding a bomb in front of a White House background, while Trump is taken away by officers and Kamala Harris is standing by an open grave reserved for Biden – shovel in hand. The text underneath the image says: “What a paradise of freedom, democracy, and sweet air.”

Artwork titled ‘失乐园·末日余晖’ ‘Paradise Lost-Afterglow’ created by ‘半桶老阿汤’ aka ‘Half Bottle Of Old Soup.’

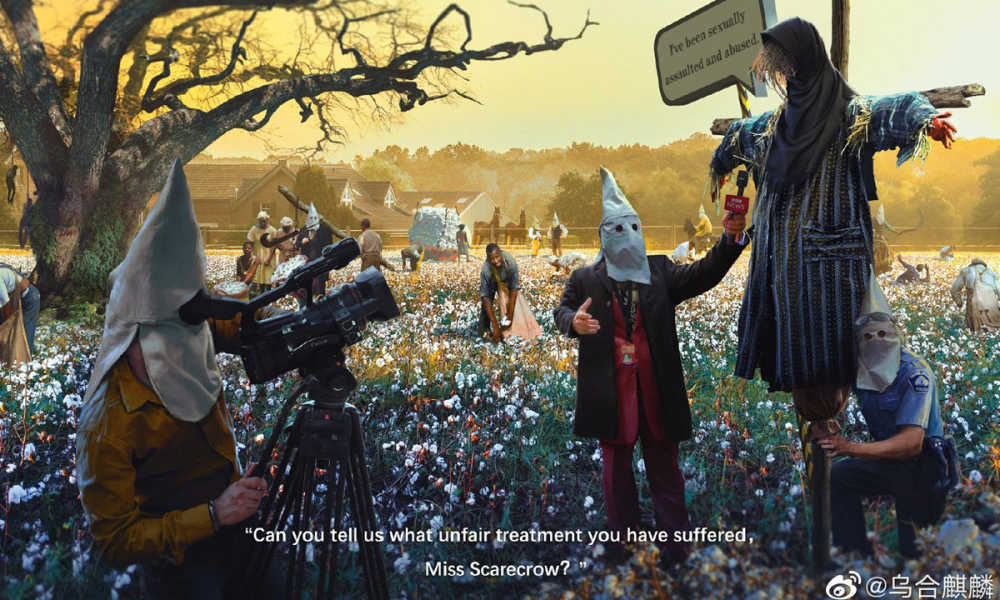

At the time of the online controversy over the Xinjiang cotton ban by the BCI in March of 2021, another digital illustration titled “Blood Cotton Initiative” made headlines for featuring (BBC) journalists in KKK-style hoods interviewing a scarecrow in a field, cotton-picking slaves in the background.

The image is a response to the allegations of forced labor and human rights abuses in Xinjiang, which various Chinese officials and state media have condemned as being ‘false,’ ‘manipulative,’ and ‘hypocritical’ in light of many western countries’ own human rights records. The image was shared on Twitter by, among others, the official account of China Daily Asia (@Chinadaily_CH) and China Daily Hong Kong (@CDHKedition).

“Blood Cotton Initiative” (血棉花) by Chinese artist Wuheqilin.

In June of 2021, another political satire made headlines, as mentioned earlier in this article. It was the image mocking the G7 members who issued a summit communique that called on China to “respect human rights and fundamental freedoms,” especially in relation to Xinjiang and Hong Kong autonomy, and also pushed for a new inquiry into the origin of the Covid-19 virus (link to pdf). The image, which is a parody of The Last Supper mural painting, is titled ‘The Last G7’ (最后的G7).

Image ‘The Last G7’ created by ‘半桶老阿汤’ aka ‘Half Bottle Of Old Soup.’

The image shows various animals sitting around the table, supposedly to represent Germany (left), Australia, Japan, Italy, US, UK, Canada, France, and India. Behind them are oxygen tanks, while the elephant on the right (India) is still receiving IV treatment and is not participating in the table talks. The Akita dog (Japan) is serving a green drink from a radioactive tea cattle while the bald eagle in the middle (US) is turning toilet paper into money. The beaver (Canada) is tightly holding on to a Chinese doll – a reference to Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou who has been in Canada ever since she was arrested during a stopover by Canadian police in 2018. On the table, there is a cake with the Chinese flag on it.

“Through this we can still rule the world,” the words above the image state, while the text on the wall in the image says: “We have freedom and democracy.” State newspaper Global Times shared and explained the political satire in an article on June 13.

The Creators Behind the Artwork

Recent Chinese political satire images circulating on social media have been labeled as ‘propaganda’ by many commenters on Twitter, who assume the images were originally published by Chinese state media outlets. But although these images were often shared by official (media) accounts, their creators are seemingly unaffiliated with state media.

Chinese social media has seen a surge of (CG) artists dedicated to creating patriotic art and political satire mocking Western powers. At this time, the two most noteworthy names are Wuheqilin and Bantong Laoatang.

‘WUHEQILIN’ 五合麒麟

The aforementioned Australian piece and the ‘Blood Cotton Initiative’ image both were created by Wuheqilin (五合麒麟), a professional computer graphic (CG) artist with over 2.8 million followers on his Weibo account, which he opened in 2009. Wuheqilin’s real name is Fu Yu (付昱, 1988) – a business owner and art director from Harbin.

Although Wuheqilin became especially famous for his controversial Australia image of November 2020, his work was featured by Chinese state media before that time. In June of 2020, Global Times (English version) called him a “Wolf Warrior artist” who “strives to use new art to spread truth and inspire patriotism.”

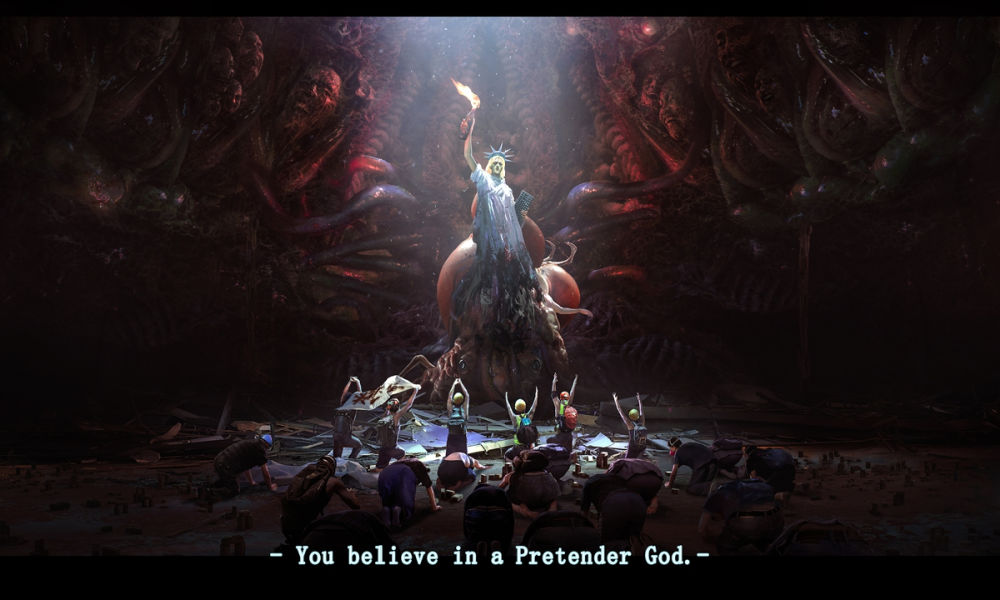

Wuheqilin published his first political artwork on his social media account in 2019, at the time of the Hong Kong protests. In this work, titled ‘A Pretender God,’ the artist takes a critical stance towards the demonstrators, showing them bowing to a monster-like figure resembling the Statue of Liberty.

‘A Pretender God’ by Wuheqilin.

Another one of Wuheqilin’s recent viral pieces is titled ‘G7’, an old-looking photograph that was a satirical comparison of the G7 foreign ministers to the leaders of the Eight-Nation Alliance that invaded northern China in response to the Boxer rebellion in 1900. This image was also shared and explained by Global Times.

‘G7’ by Wuqihelin.

Wuheqilin clearly focuses on showing the dark side, hypocrisy, and supposedly bad intentions of Western powers in international politics. Noteworthy enough, he often uses English phrases in his work to emphasize his point, which may suggest he also intends for his art to be noticed by media and politicians outside of China.

Although Wuheqilin is most famous for political satire mocking Western powers, he also makes non-satirical patriotic art, such as the piece he dedicated to Chinese agronomist Yuan Longping (袁隆平), China’s ‘Father of Hybrid Rice,’ who passed away in May of 2021.

“I Always Had Two Dreams” “我一直有两个梦想” by Wuheqilin.

Over the past year, Wuheqilin and his work are often praised by Chinese official media outlets. It is often shared by English-language state media, or retweeted by Chinese officials or media accounts that are active on Twitter. Together with the fact that Wuheqilin uses English in his artwork, his work has gained major attention both in- and outside of China.

‘HALF BOTTLE OF OLD SOUP’ 半桶老阿汤

The creator of ‘The Last G7’ image and the White House image is active on social media under various names. On Weibo, where he has over 39,000 followers, the artist is known as @半桶老阿汤 (Bàntǒng lǎo ā tāng). On Twitter, he has an account under the name ‘Half Bottle Of Old Soup’ (@Half_soup), a direct translation of his nickname. The artist also has a site under the name Henry Yu. His webshop is under the ‘Laoatang’ nickname, which we will use here.

Laoatang is a concept designer and computer graphic artist from Beijing. On his Weibo account, the artist has been sharing artwork by himself and others for years. Like Wuheqilin, he has an online cloud link where people can download artworks for free, but he also has a site where people can support him by buying digital art files for the small price of 10-15 yuan ($1.5-$2.5).

Like Wuheqilin, Laoatang’s artwork is also often focused on mocking the supposed hypocrisy of Western powers regarding international affairs involving China. ‘The Last G7’ was the first work by Half Soup to make (international) headlines, but he previously did many other works in response to political affairs.

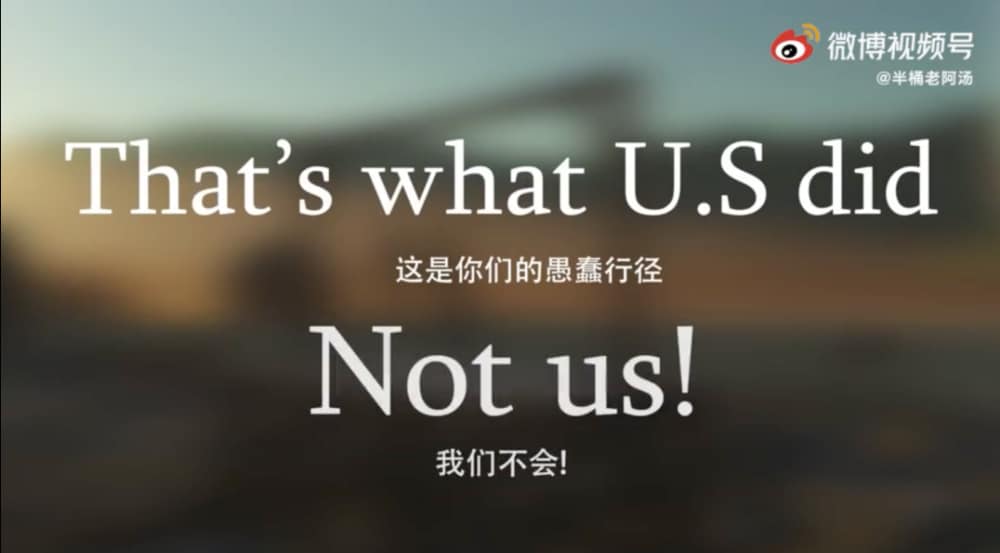

His work ‘That’s What U.S. did'(‘这是你们的愚蠢行径,我们不会’) was published at the time when news over the BCI [Better Cotton Initiative] Xinjiang cotton ban over forced labor concerns made waves in China.

‘That’s What U.S. Did’ by 半桶老阿汤

The image is part of a computer graphic video that shows black slaves working in American cotton fields while singing ‘My Lord Sunshine Sunrise.’ The next scene shows how one black man is held at gunpoint by a white hooded figure, a scarecrow with a BCI logo showing in the foreground. The words “That’s what U.S. Did, Not Us!” come up while two black figures can be seen hanging from the gallows.

In a different style, Laoatang has also created various other political satire illustrations. One from June 2021 is called ‘Investigate Thoroughly! Except Here’ (‘彻查!除了这儿’). It shows members of the WHO research team standing in front of the American army biochemical lab at Fort Detrick which is closed and guarded by Biden. In the background, there’s the scenery of a happy and open Wuhan city.

‘Investigate Thoroughly! Except Here’ (‘彻查!除了这儿’) by 半桶老阿汤 / Half Bottle of Old Soup

The illustration is a response to U.S. calls for a thorough investigation into the origins of the novel coronavirus in China, while a possible link between the Fort Detrick institute and the COVID19 pandemic are allegedly ignored. This image was also shared by the Communist Youth League on social media.

OTHERS & INTERTEXTUALITY

Online creators such as Wuheqilin and Laoatang move in certain Chinese social media circles of artists producing work in similar genres who share each other’s work and comment on it. At times, there is also some kind of intertextuality or connection between these artworks.

A good example of this intertextuality is the work by the artist who is active on Weibo under the name ‘钢铁时代2011’ (Gangtie Shidai 2011). In December of 2020, they published the artwork below that reflects on the international commotion involving the Australian soldier image by Wuheqilin, which was tweeted out by Chinese official Zhao Lijian.

“Damn it, they know what we’ve done” by @钢铁时代2011 [Gangtie Shidai 2011].

The image shows artist Wuheqilin holding up one of his artworks relating to the alleged Australian war crimes in Afghanistan, while Zhao Lijian is holding up the other image by Wuheqilin. In the front, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison is depicted turning his back to the images, with the sentence: “Damn it, they know what we’ve done.”

During the controversy over the BCI ban on Xinjiang cotton, there was also an outpour of online (unofficial) political art. Beijing illustrator Yang Quan @插画杨权 (1990) is also among those creating online political/patriotic art. He published an image titled “Cotton is Soft, but China is Strong.”

‘Cotton is Soft, But China is Strong’, by @插画杨权.

The dog has the letters “H” and “M” coming from his bloody mouth, referring to fashion chain H&M which was one of the major Western brands publishing a statement regarding the ban on Xinjiang cotton (read more here). Again, as in most of the recent works produced by the artists in this genre, the message of the image is reinforced through a text in English, suggesting the work is also meant for an international audience to understand.

In Between Censorship and Propaganda

Propaganda is part of Chinese media, and a ‘new’ kind of propaganda has been part of Chinese social media propaganda efforts over the past few years (also see here, here, here, here).

But separated from those mainstream, more centralized propaganda efforts, the artists mentioned in this article are part of a ‘new wave’ of political satire on Chinese social media because:

– They are independent artists and/or not officially part of state media outlets or the CCP Propaganda Bureau.

– Their style is very different from official (online) propaganda posters and imagery.

– Their works are labeled as ‘art’ and have definite artworks qualities; they are unique, are made with skill and technique, and are filled with symbolism and detail.

– Their works are praised and welcomed by state media outlets and/or government officials, as these are shared and propagated through multiple official channels.

– These artists and their creations are widely celebrated and praised by Chinese social media users.

The phenomenon of artists who are unrelated to official agencies creating political art that is then used as a tool for propaganda is not unique in the history of Chinese propaganda or that of other countries, but it is very noteworthy in the context of the short history of social media in China, where political satire is often targeted at Chinese government officials and policies and therefore censored.

Perhaps you could say it is not surprising at all that the political satire we see most in Chinese social media today is directed at foreign leaders and Western powers, since any images mocking the Chinese government would be censored immediately.

But to solely interpret these political images through this one-dimensional view would not do justice to the artwork, the artists, nor to the art aficionados, since there are several influences at play within the creation of this genre.

> Digital Art & Nationalism

There are many young artists in China today who are patriotic and nationalistic, and who use art as a way to express their political views. They do so in various ways, through personal websites, social media, cloud downloads, etc, providing an alternative to official, controlled media sources. Propaganda sometimes becomes art, and art sometimes becomes propaganda. These dynamics do not automatically turn these artists into ‘Chinese trolls,’ as some foreign media labeled them.

Artists such as Wuheqilin or the aforementioned artist named Yang Quan all belong to the post-80 generation. In this current, post-Mao generation, you find a “fourth generation” of nationalism, as described by Peter Hays Gries in China’s New Nationalism. This nationalism is very much alive in China’s online environment, and it is fused with anti-western sentiment that partly builds on the “one hundred years of humiliation” of China at the hands of the West (Zhang 2012, 2). Although this generation, that grew up amid China’s rapid economic growth, did not directly experience the past humiliations upon which their nationalist narratives are constructed, this history remains central to understandings of Chinese national identity and its place in the world today (Wang 2-11).

As pointed out by Tao Zheng (2012), the articulation and promotion of nationalist views by individuals and groups independent of the state have been a significant part of Chinese online culture for many years, with several online movements and campaigns focusing on pointing out “western arrogance and prejudice.” The current wave of political digital art is just another form of expression of this type of “cyber nationalism.”

> Building Communities

Another reason why it would be too crude to simply label China’s recent online political satire as ‘propaganda’ is because it has emerged from a dynamic digital environment where netizens engage in a participatory activity of creating, sharing, commenting, recreating, connecting, etc. – and it is through these practices that the artworks become meaningful.

In ‘The Networked Practice of Online Political Satire in China’ by Guobin Yang and Min Jiang (2015), the authors argue that the sharing and circulation of online political satire in China is a “networked social practice” that is actually more important than the meaning and significance of the content itself. It is a grassroots political expression that, in their mode of unofficial network operation, could be seen as “popular mobilizations against power” (216). Yang and Jiang also emphasize the social function of political satire, where the reception is just as relevant as the production.

> A Fine Line

In the end, the question of whether these works are grassroots digital artworks or official propaganda pieces is perhaps not one of either/or: they are both. They saw the light as digital artworks and then became tools within a framework of official propaganda once they were praised, shared, and used by Chinese state media and officials to project their own strategies.

The creators of these artworks, however, walk a fine line. When their artworks no longer suit the strategic interests propagated by official channels, they are still at risk of being censored within the highly controlled digital environment they operate in. In that case, their online influence, magnified by official actors, could actually be held against them.

For now, artists such as Wuheqilin are thriving on Chinese social media. In his last post, Wuheqilin drew his own conclusion about the current state of China’s online environment, writing:

“For the public intellectuals and those with vested interests who once held on to the power of speech, these are perhaps the darkest times, because their “decade-long campaign for Enlightenment has been lost.” But for ordinary Chinese netizens, for those who love this country and believe in it, we have unprecedented confidence, creativity, and cohesion. These are the best of times, and we are marching towards the brightest future.”

By Manya Koetse (@manyapan)

Follow @whatsonweibo

With special thanks to Piervittorio Milizia.

References

Gries, Peter Hays. 2004. China’s New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy. Berkely and London: University of California Press.

Shao Li, Liu Dongshu. 2019. “The Road to Cynicism: The Political Consequences of Online Satire Exposure in China.” Political Studies 67(2): 517-536.

Yang, Guobin and Min Jiang. 2015. “The Networked Practice of Online Political Satire in China: Between Ritual and Resistance.” The International Communication Gazette 77(3): 215-231.

Zhang, Tao. 2012. “Anti-CNN and ‘April Youth’: Anti-Western Sentiment in Youth-oriented Chinese Online Media.” In Hernandez, L. (ed.), China and the West: Encounters with the other in Culture, Arts, Politics and Everyday Life,

Cambridge Scholars, 1-16.

Zheng Wang. 2012. Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Featured image created by What’s on Weibo, highlighting and using parts of various digital artworks by @五合麒麟, @半桶老阿汤.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at [email protected].