Gone Fishing . . . for a New Inuit Print | by Cleveland Museum of Art | CMA Thinker | May, 2022

[ad_1]

By Amanda Mikolic, Curatorial Assistant

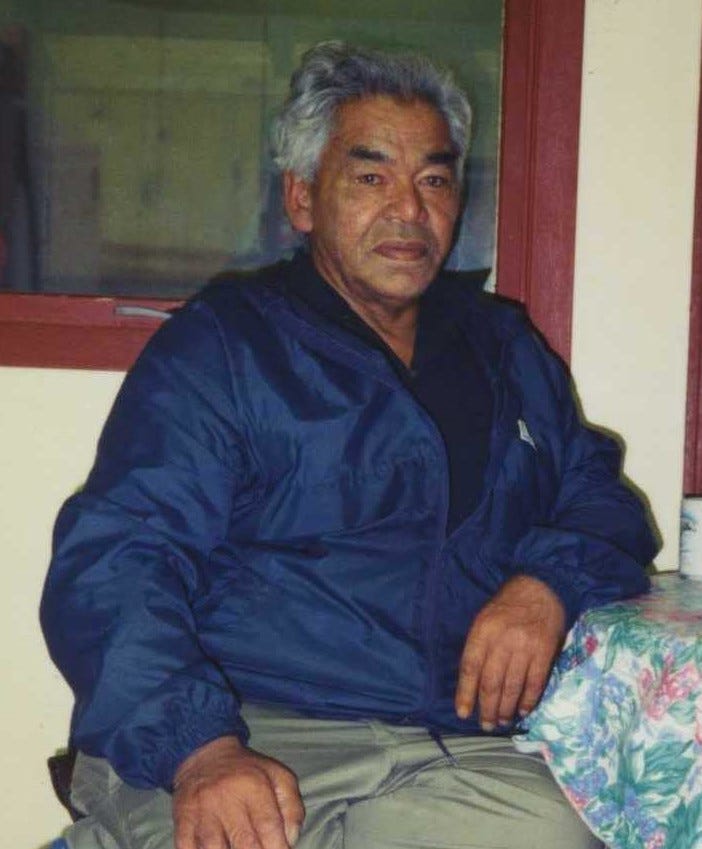

New in gallery 231 is Devil Fish, a stonecut print by Alec (Peter) Aliknak Banksland (1928–1998); Aliknak, who preferred to be called by his Inuit name, spent most of his life in Ulukhaktok (previously Holman), a village north of the Arctic Circle in Canada’s Northwest Territories. In 1961, he was a founding member of the Ulukhaktok Arts Centre (then the Holman Eskimo Cooperative), an important printmaking cooperative originally established to provide the Inuit with a way to earn income and to remember and record their traditional ways of life at a time when those were fast disappearing.

This was because between 1950 and 1975, the Canadian government forcibly relocated many Inuit, who for centuries had lived as semi-nomads in seasonal hunting and fishing camps, into permanent settlements. The initiative was intended to make it easier to provide education, health care, and other services. But the Inuit were not consulted, services were inadequate and misguided, and the Inuit often struggled to adapt to a completely new way of life in villages far outside the economic mainstream. The Canadian government recently renounced and apologized for these and others of its Inuit policies.

It was in response to this situation — the need to create jobs to support Ulukhaktok’s growing Indigenous population — that in 1961 the French missionary Henri Tardi and five Inuit artists including Aliknak each contributed ten dollars to form an arts cooperative, supplementing their investment with money borrowed from Canada’s Eskimo Loan Fund, which was intended to provide new economic opportunities to the Inuit. The cooperative was one of several formed for similar reasons and one of the most successful; others include the cooperatives at Cape Dorset, Povungnituk, Baker Lake, and Pangnirtung. Among the first artworks sold by the Ulukhaktok cooperative were carvings, but experiments in printmaking with sealskin stencils soon began.

In 1963, Aliknak contributed to a selection of ten prints that the village sent to the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council (CEAC), a government-appointed jury that approved Inuit print selections until it was disbanded in 1989. CEAC rejected the prints, deeming Aliknak’s work as having too much “southern influence”; in other words, he was too proficient in the use of such western graphic conventions as overlapping, foreshortening, and single-point perspective. The judgement was a source of bewilderment and disappointment to the artists; discouraged, Aliknak took a break from printmaking. In retrospect, CEAC’s preference for artworks free of western or Euro-Canadian influence extended the legacy of colonialism by forcing Indigenous people into a “primitive” model that the government thought to be more authentic and marketable.

The same year, the federal government sent an advisor to Ulukhaktok to help with further arts development. In 1964, Indigenous artists began to produce stonecut prints using local limestone. By 1966, when Aliknak returned to printmaking, the artists of Ulukhaktok were beginning to receive international attention after releasing a collection of thirty limited-edition prints. Printmaking soon became the village’s main source of income, and the cooperative was able to quickly repay the loan they had received and flourish on their own.

In general, the cooperatives, some of which are still active, release annual portfolios of prints made up of contributions by members. Though the process varies somewhat, artists usually work at home to create original drawings on paper, which they sell to the cooperative. If selected for printing, the drawings are transferred to stone, often by a different artist; in Ulukhaktok, one such artist was Harry Egotak, who had been involved in printmaking since its earliest days. Once the image is carved in relief on the stone, the raised surfaces are inked and a sheet of paper is pressed onto the stone, then pulled away. After a limited run, the stones are destroyed.

Aliknak used this technique to create Devil Fish, which whimsically captures a fisherman clad in a parka, a typical Inuit

garment made from animal skin, peering at his open-mouthed prey through a hole in the ice. Built on striking color contrasts and silhouettes, the composition is attentive to balance around a strong center — for instance, the fisherman’s outspread feet echo the upturned tails of the fish. As the print reveals, Aliknak’s favorite subjects were scenes from traditional Inuit life, which he interpretated and rendered in meticulous detail. Aliknak’s original drawings were executed in full color with felt-tip pens and are often painterly; he sometimes carved the stone blocks for printmaking himself.

In Inuinnaqtun, a dialect of the Indigenous Inuit language, ulukhaktok means “where there is material for ulus,” in reference to the copper and slate from nearby bluffs that are used to make all-purpose knives (ulus) that have practical purposes and, for Indigenous women, cultural meaning tied to tradition. In fact, the mark that distinguishes prints from Ulukhaktok includes the image of a ulu; it is embossed on the bottom of Aliknak’s prints.

Another example can be seen on a print from the Cape Dorset cooperative featuring a woman holding a ulu with a small child strapped to her back. Like Aliknak, the creator, Pauta Saila (1916/7–2009), was a multidisciplinary artist, working both as a carver and printmaker.

Aliknak’s involvement in printmaking ceased by the 1980s, when the Ulukhaktok cooperative abandoned stonecut prints due to the poor quality of the local limestone and adopted different printmaking techniques, including stencil, lithography, and woodcut. Although a new generation of artists continues to work in Ulukhaktok, they have not created an annual print collection since 2000, preferring to focus on special commissions, making current work from the community rare. To learn more about Aliknak and Inuit printmaking cooperatives, visit the following websites, including one that features interviews with Aliknak and his family. Devil Fish will be on display in the Native North American art gallery 231 until November 2022.

Further resources to explore this topic:

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuit-printmaking

https://inuvialuitdigitallibrary.ca/items/show/281

https://inuvialuitdigitallibrary.ca/items/show/400

https://thediscoverblog.com/2021/01/04/the-canadian-eskimo-arts-council-defining-inuit-art/

[ad_2]

Source link