By his own cheerful admission, Anton Corbijn’s relationship with Depeche Mode did not get off to a flying start. It was 1981 and Corbijn was the NME’s new star photographer, having previously been lured to the UK from his native Netherlands by the sound of British post-punk, particularly Joy Division. His black and white portraits became iconic images of that band’s brief career, and Corbijn had gone on to take equally celebrated shots of everyone from Captain Beefheart to David Bowie.

Depeche Mode, on the other hand, were a synthpop band from Basildon, Essex, whose career already appeared to be in trouble after only two hit singles. Ominously, Vince Clarke, the band’s chief songwriter, failed to turn up for one of Corbijn’s shoots, and would announce his departure a couple of months later.

Not that Corbijn was bothered: he didn’t like Depeche Mode, preferring “more guitar-oriented stuff”. He had already seen them live, but they left so little impression he forgot. When the band – reassembled with Alan Wilder replacing Clarke and Martin Gore installed as songwriter – asked to work with him again, he repeatedly declined: “It’s just more pleasing if you take photographs of people whose work you admire,” he shrugs, over a Zoom call from his studio in The Hague. Then, five years after their initial meeting, he finally agreed to make a video for their single A Question of Time, but only because he fancied a trip to the US. “I realised they had changed,” he says, “and somehow I realised how good their music and my visuals actually went together. But it was a surprise.”

It was the start of a 40-year partnership that grew from taking photos and directing videos to Corbijn becoming the band’s visual director, designing everything from their logos to their album sleeves to their stage sets – an association that’s celebrated in a new book, Depeche Mode by Anton Corbijn. In retrospect, it looks like an obvious pairing. A band whose debut album had been dismissed by Rolling Stone as “PG-rated fluff”, Depeche Mode became increasingly dark and ambitious musically as the 80s progressed. They needed visual gravitas to match, and Corbijn’s grainy black and white images and hand-painted album sleeves certainly gave them that. “I felt people associated synthesiser music with being technical and emotionally distant,” he says, “and I felt they had soul. I think I had an approach that’s more in that direction, and that made the difference.”

Moreover, Gore’s songs frequently examined faith and belief – Blasphemous Rumours, Personal Jesus, virtually the entirety of 1992’s Songs of Faith and Devotion album – a subject that chimed with Corbijn’s upbringing. “My father was a pastor, and so were my uncles and grandfathers,” he says. “Up until the age of 10 or 11, I wanted to become a missionary. Until I read that in New Guinea, two missionaries got eaten, and that was off the table. I didn’t know what to do with my life until I was 17 and got a camera in my hand. I guess I realised that Martin gets some energy and ideas out of religious writing and the Bible. Combined with my background, I think that felt very natural.”

Corbijn also seems to have been blessed with an acute insight into what made Depeche Mode work. In the late 80s, he published a book called Strangers, featuring photographs of the band in Prague and the Mojave Desert, ostensibly to emphasise their burgeoning popularity both in eastern Europe and the US. In the former, they look like austere European electronic artists; in the latter – stripped to the waist, strumming guitars amid the cacti – like a traditional rock band. The fact that they were actually both feels central to their vast success. “Totally,” he nods. “Dave [Gahan] is a rock’n’roll guy, Martin much less so. I think that’s the tension in the band – which direction do we go in with this song or that song. He’s a great frontman, Dave, he’s fantastic. At his age, and having been clinically dead, it’s nothing short of a miracle that he performs and sings as well as he does.”

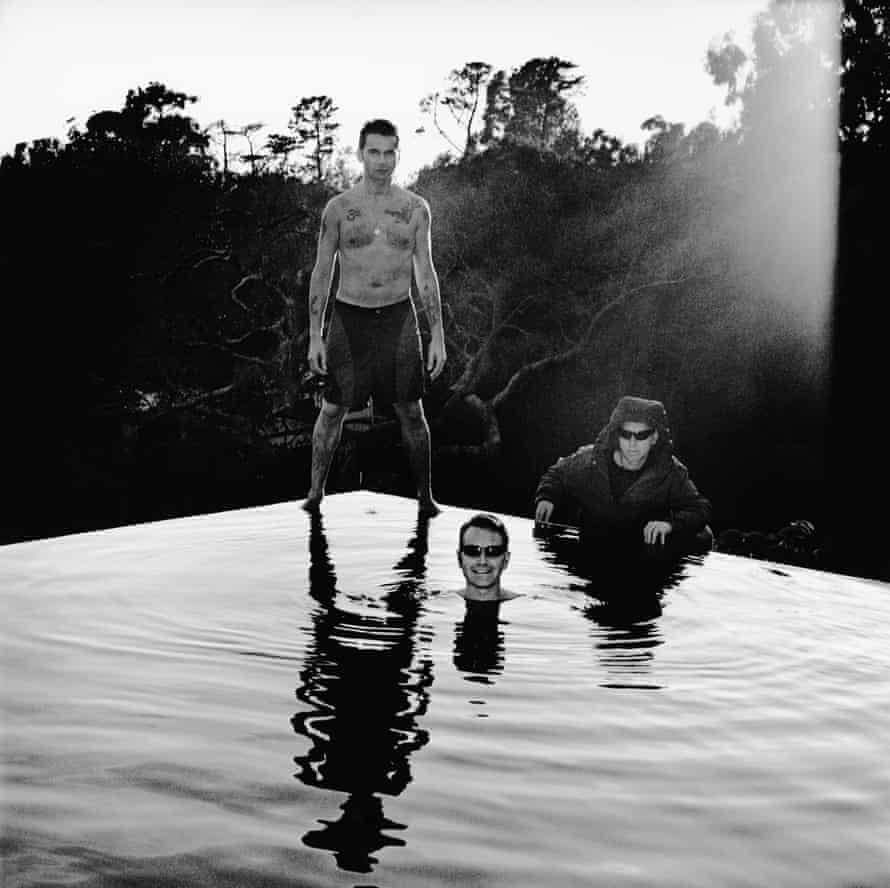

![‘[It’s] as if he’s praying for Dave’ … Daniel Miller (right), and Dave Gahan.](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/3c6367737799f25a97504e6f506458a3ef4368d8/0_0_7816_7874/master/7816.jpg?width=300&quality=45&auto=format&fit=max&dpr=2&s=1d53d6e88e8f3b6ad90591b84a85cf09)

Gahan “clinically died” in 1996, his heart stopping for two minutes after taking a cocktail of heroin and cocaine in an LA hotel. It was the culmination of a period during which Gahan descended into addiction, had a drug-induced heart attack on stage and attempted suicide. Gore succumbed to alcoholism and began having stress-induced seizures, Wilder quit the band and Alan Fletcher suffered a nervous breakdown, all while Depeche Mode were at the zenith of their success. Violator, from 1990, had sold 7.5m copies; Songs of Faith and Devotion went to No 1 on both sides of the Atlantic; an ensuing tour lasted 14 months, the band performing on a stage set Corbijn had designed “without knowing the limitations of what you could do”. It involved two stages, one on top of the other, and proved so costly that it was abandoned halfway through the dates. “But it was amazing while it lasted,” laughs Corbijn.

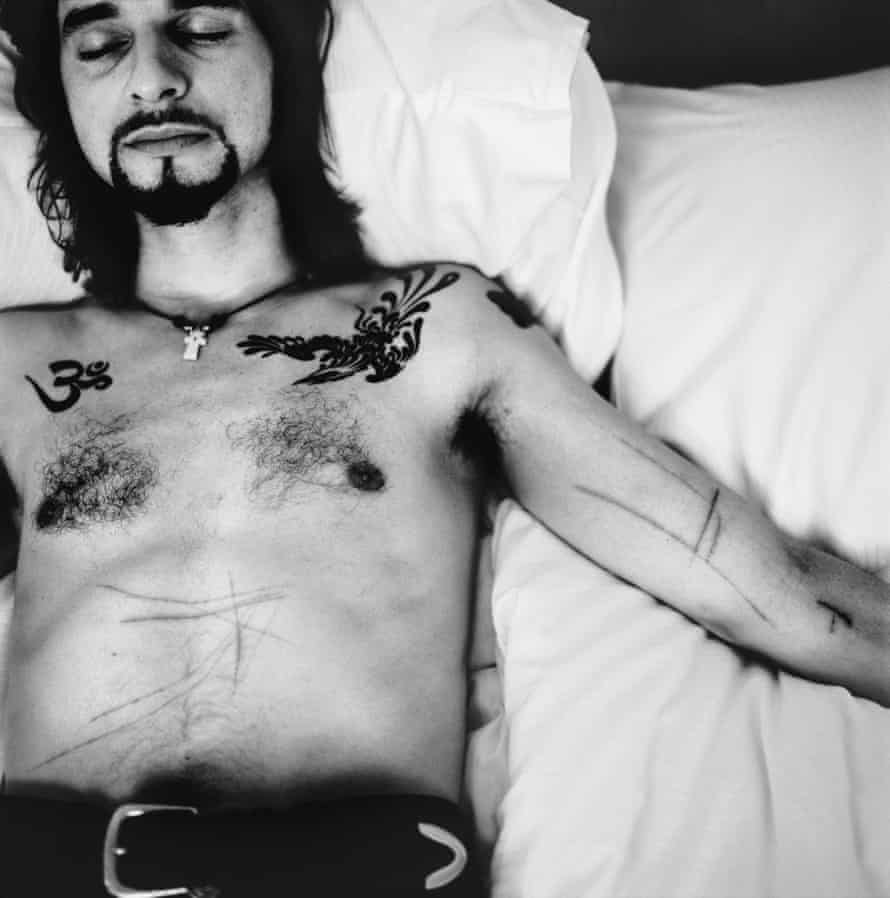

Two photos in the book sum the period up perfectly: in one, “just a snapshot really”, an emaciated-looking Gahan stares out of a window while, outside, Mute Records founder Daniel Miller appears to clasp his hands “as if he’s praying for Dave”; in another, Gahan lies topless on a hotel bed after a gig in Frankfurt, his stomach and arms a mass of scars and scratches. “Some of them are because he dived into the audience during the show, and some of them are self-inflicted,” says Corbijn. “It really sums up, I think, the lowest point of Depeche and Dave: that was just before he went into the spiral that ended with him clinically dead. I showed it because obviously he came out of that, so it shows you the depth and the power he had, the discipline, to get out of that.”

Corbijn has continued working with the band to the present day – he directed the 2019 documentary, Spirits in the Forest, about the “very intense” relationship Depeche Mode’s fans have with the band’s music, despite his own career taking him from photography to Hollywood. Control, his acclaimed biopic of Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, began a directing career that’s included working with George Clooney on the thriller The American, the late Philip Seymour Hoffman on the John le Carré adaptation A Most Wanted Man, and Robert Pattinson on the James Dean biopic Life. It is, he concedes, a curious relationship he has with Depeche Mode: he has no contract, no job title. “It goes from one project to the next and I assume I’m involved.”

He says he only realised he was something more than a favoured photographer and director when the band agreed to his idea for the video for the 1990 single Enjoy the Silence – despite the fact that they hated it. “I thought, ‘OK, they care for me or care about my ideas, they trust it somehow.’” The video, which featured Gahan as a king carrying a deckchair through a variety of landscapes, became hugely successful on MTV, propelling the single into the US Top 10. Its imagery subsequently inspired the lyrics of Coldplay’s Viva La Vida, for which Corbijn also directed a similarly themed video.

For the most part, he says, Depeche Mode just leave him to get on with it, a marked contrast to his other celebrated regular clients, U2. “U2 are a band who believe in meetings, so everything has a meeting. With Depeche, it’s an exception to have a meeting at all. When I did visuals for The Joshua Tree 30th anniversary tour, I also filmed the show in Mexico City. After the concert, U2 all came to look at the footage. At midnight! For two hours! I mean, Depeche – you couldn’t get them to watch a minute. It’s an incredible difference in attitude. But that’s also the charm of Depeche. They don’t do many interviews, there’s no big plans, they just make a record and tour.”

Besides, he says, their laissez-faire arrangement works. “I think that lack of reining me in forces me to be great,” he says, “because I want to be great for them. I don’t want their trust to be an accident. I want their trust to be earned.”

Depeche Mode by Anton Corbijn is out now, published by Taschen.

This article was amended on 1 June 2021. An earlier version referred to photographs of Joy Division in snow-covered Manchester, and said they were taken by Corbijn. They were actually taken by Kevin Cummins, and this reference has been removed.

-

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email [email protected]. You can contact the mental health charity Mind by calling 0300 123 3393 or visiting mind.org.uk