[ad_1]

“I can’t draw a stick figure.”

“I can’t even draw a straight line.”

“But I don’t know how to draw!”

“I can’t draw to save my life.”

If you have heard these gloom-and-doom phrases, they have come from students and adults alike. The question is, where do people get the idea there is only one way to draw? And who said straight lines or stick figures are the metrics by which good drawing is measured?

Let’s look at contemporary approaches to teaching drawing that break drawing myths for students of all ages.

We will examine some of the defining properties of drawing practices. We will also expand upon the sage ideas of Betty Edwards to explore researched strategies by scholar, artist, and educator Andrea Kantrowitz. Through Kantrowitz’s methods, you can stretch students’ understanding of drawing as a tool. These strategies can help your students develop self-confidence and deeper engagement.

What is drawing?

A quick web search will yield definitions of a fixed set of ideas. For example, a drawing is a graphic representation, the depiction of an image, or an inscription of lines on a flat surface made with a pen or pencil. Collins Dictionary even suggests drawing is “delineating form without reference to color.” In what ways can we expand upon such limiting definitions?

In today’s world, drawing applications are stimulating. Like Pushing paper: contemporary drawing from 1970 to now from the British Museum (2020–2022), new exhibitions attempt to redefine drawing methods and materials. In this exhibition, curator Isabel Seligman seeks to challenge traditional conceptions of drawing. Seligman juxtaposes traditional drawing tools with “unusual materials from wax and gold to rattlesnake poison” and features “processes such as burning, cutting, scratching, sticking, writing and sewing.” In this survey, Seligman shows the answer to “What is drawing?” is not clear-cut. Yet, this open question is where things get exciting.

In 1967, conceptual artist Richard Long blurred the lines between photography, performance art, sculpture, and drawing in A Line Made by Walking. His footprints traced a line in the grass by retreading the same line across a field. “Is this a drawing?” you may ask. It’s a mark on a surface, right? This piece embodies Paul Klee’s famous quote, “A line is a dot that went on a walk.” Long’s line, etched into a field, offers a new way of learning about space. His act of drawing stretches the definition of what a drawing can be.

As art educators, we have the unique opportunity to highlight the endless potential of drawing to students of all ages. We can break the mold by questioning the what, how, when, and why. Drawing doesn’t have to be relegated to a desk. Drawing is a teachable process that offers possibilities beyond mere skill development. Drawing processes can also inform cognition, reflection, observation, connection, creativity, and collaboration.

Who can draw?

We owe a lot to Betty Edwards for her seminal 1979 text, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. She explored a range of strategies to loosen up artists by re-examining visual perception. Upside-down drawings, blind contours, timed sketches, non-dominant-hand drawings, and profile portrait drawings name a few of the strategies she shared. In this book, Edwards articulates how anyone can learn to draw with average eyesight and average hand-eye coordination. Edwards sets the stage for learning by dispelling the myth that drawing is a magical gift.

Why draw?

In the article, Drawn To Discover: A Cognitive Perspective, Andrea Kantrowitz inquires, “How can the act of drawing help drawers think through ideas and experiences?” By helping our students broaden their understanding, we can encourage new entry points for drawing.

Drawing is everywhere, and the reasons for making drawings are many. Some people draw as a form of relaxation or meditation, while others draw to document what they see. People from several professions draw to articulate their ideas as tools for communication. Mike Rohde, UI designer and author of The Sketchnote Handbook, explores the power of drawing as a visual thinking tool. Drawing often prompts quick idea generation, enables exploration of alternative possibilities, and encourages discussion. In 10 Reasons Why Drawing Is Good for You, Julianna Wells considers drawing a tool for analysis, understanding, concentration, and coordination.

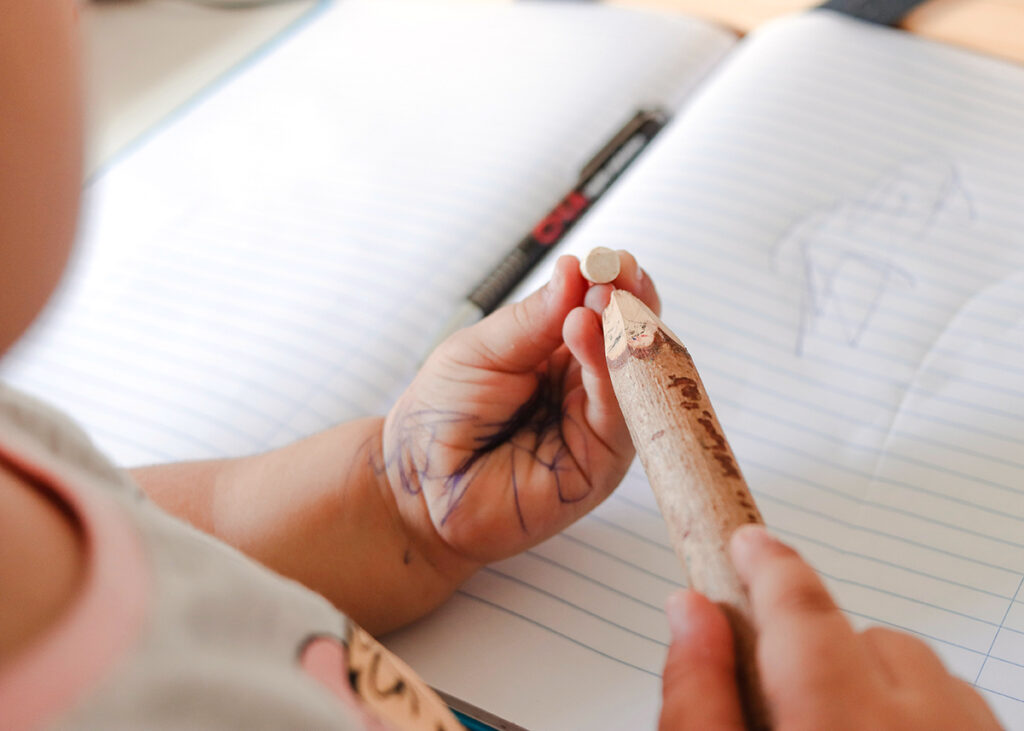

Drawing is something humans have done since time began. In Kantrowitz’s 2017 TedX talk, she urges, “I’m determined to remind people that we all draw. We all started out drawing. Before there was paper, we drew in the sand, we drew in the dirt. Across all cultures, throughout human history, we’ve drawn.”

You won’t need to spell out the rationale of drawing to entice a young child to draw. Early childhood educators know the intrinsic form drawing takes in the classroom. From coloring on the walls and outside of the lines to drawing shapes in the sand, young learners don’t question their compulsion to draw. Yet, as students grow older, reticence sets in. Many students become discouraged when they struggle to represent an image true to life. Some lose their confidence to draw altogether. How do we bring them back? How can we teach our younger students to avoid “I can’t” statements?

What are the purposes of drawing?

To address several burning questions about drawing, Kantrowitz produced a series of videos in collaboration with the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts. Starting with observational drawing, then moving towards abstraction and collaboration, these videos explore nine different ways of drawing. When students understand drawing as a tool instead of just a skill, they will start to see a bigger picture. Next, we will investigate several accessible strategies for your students.

While all nine of Kantrowitz’s strategies are worthy of investigation, let’s unpack five drawing tools that may be less familiar.

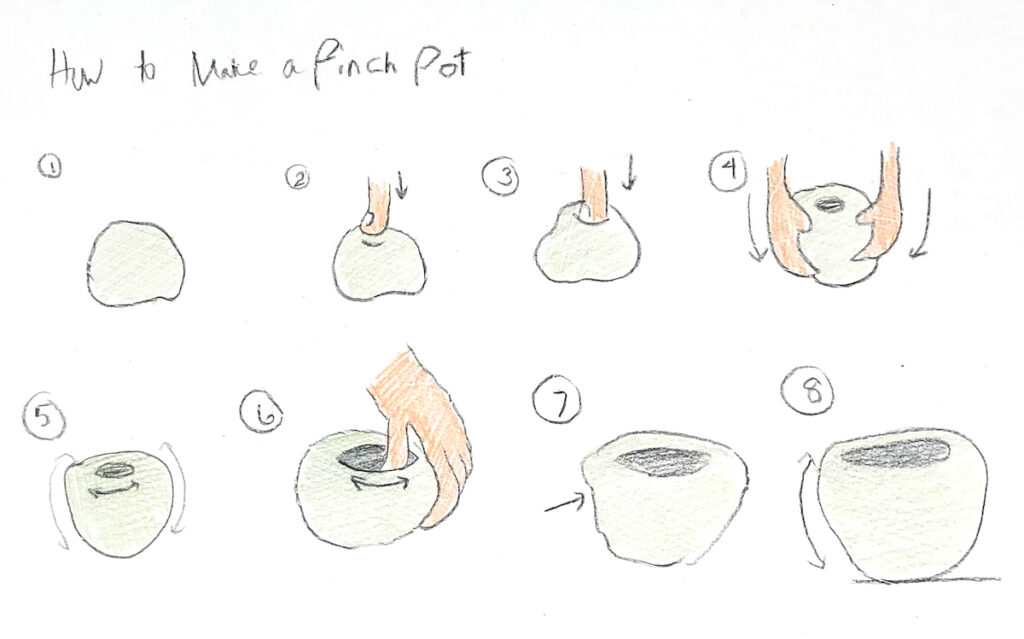

1. Drawing as a Tool for Planning

In her short video, Ways to Draw #4: Drawing to Plan a Course of Action, Kantrowitz asks students to draw a series of steps. In the schematic, students outline a series of actions to illustrate how to make an origami form. How might this apply to your students?

This strategy is practical and has numerous applications. Perhaps an architect wants to envision a series of steps in a new design, or a fashion designer may want to communicate specific actions for how to assemble a garment. Engineers, scientists, chefs, and writers often use drawings to plan their next steps. Use this planning tool to help students connect drawing to other disciplines.

2. Drawing as a Tool to Explore Moods and Emotions

We have already seen how drawing is often associated with lines. In the fifth drawing strategy, Ways to Draw #5: Connecting Universal Moods and Emotions Through Mark-Making, Kantrowitz offers an open-ended activity to generate lines and marks. By prompting students with a series of words, such as “Focus,” “Joy,” and “Flexibility,” students must draw each word on a different piece of paper. At the end of the mark-making activity, group the drawings. Through discussion and reflection, students see how their different marks represent moods and emotions.

You can maximize this drawing tool by tying it into a unit where students need to access their emotions to engage in their work authentically. You may choose to use this as a pathway for helping students develop their voices. Mark making is individual and personal. Utilize this tool for building self-confidence and independence.

3. Drawing as a Tool for Empathy and Imagination

In Ways to Draw #6: Drawing Someone Else’s Memory, Kantrowitz sets students up in pairs. One student describes a personal memory to their partner while sitting back to back. Without looking at the drawing, the storyteller must use words to illustrate the story. Meanwhile, the drawer must inhabit the story of their peer. The drawer imagines their peer’s story as they illustrate it. At the end of the process, the storyteller’s narrative is reflected back to them. They have a window to see how another person interprets their memory.

Visual artist William Kentridge explains how drawing enables compassion. In the Art 21 episode, Pain & Sympathy, Kentridge elaborates that, when making a drawing, sympathy can develop as an embodiment of the process. In essence, drawing can serve as a tool to connect with the experience of others. Give Kantrowitz’s strategy a try to develop thoughtful peer-to-peer connections in your classroom.

4. Drawing as a Tool for Collaboration

Unlike in other artistic disciplines, collaboration is not baked into visual arts, such as dance, music, and drama. To highlight the potential for collaboration, why not try out drawing as a tool?

Kantrowitz shares two collaborative methodologies in Ways to Draw #7: Collaborative Drawing. In the first method, students take turns working on a large piece of paper. As each student takes their turn, they intuitively add to the marks laid down by the previous person. As a second approach, Kantrowitz encourages a planned composition. Students thoughtfully combine their drawings to create something new.

Activities like these can foster a spirit of community before students get to know each other. However, you can implement collaborative drawings to build new bridges and fortify existing peer relationships in your classroom mid-year.

5. Drawing as a Tool for Communicating

Kantrowitz once again uses language as a starting point for Ways to Draw #9: Visually Communicating Abstract Concepts. Each student is randomly provided with a word written on a small slip of paper. They are instructed to keep their word a secret from their peers. “Allude,” “Recapitulate,” “Speculate,” and “Embrace” are some of the terms she provides to her adult students. Each student takes time to illustrate the word using representational or abstract imagery on a small scrap of paper.

Once finished, Kantrowitz offers a collaborative extension. In pairs, students share their drawings without revealing their words. Together, they use drawing as a tool to elaborate upon the connections they see between their two images. Finally, the students share their words and add to their drawings to further the visual relationships they have identified.

This final strategy offers a meaningful way for students to explore drawing as a tool for communication. Also, students use critical thinking to synthesize disparate images and create visual connections. Through collaboration, students construct and explore complex meanings.

Introduce new strategies to shift students’ perceptions.

From young to old, new drawing strategies can have a powerful impact on your students’ understanding of drawing. Drawing offers a meaningful way to generate and visualize ideas. Drawing can help students develop new insights. Students can collaborate and empathize through drawing or synthesizing abstract concepts. Drawing also holds incredible potential as a tool for observation, documentation, and representation. We owe our students to look beyond these conventions to boost motivation and self-confidence.

Here are some further resources as you rethink drawing and its purpose in your classroom:

Books:

Articles:

What innovative drawing strategies do you currently use?

Which of the above strategies might challenge your students’ mindsets about drawing?

[ad_2]

Source link